Rotator Cuff Impingement

Rotator Cuff Disease / Impingement Syndrome

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the rotator cuff in the shoulder?

- What is impingement syndrome?

- How does impingement syndrome relate to rotator cuff disease?

- Why do some people develop impingement and rotator cuff disease and others do not?

- Other than impingement, what else can cause rotator cuff damage?

- What symptoms does a patient have when the rotator cuff is injured?

- How is the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease proven?

- What is the initial treatment for rotator cuff disease and impingement?

- What is the second line of treatment if pain and weakness persist?

- If the rotator cuff is already torn, what are the options?

- What will happen if the rotator cuff is not repaired?

- How is a major injury to the rotator cuff tendon repaired surgically?

- How is my shoulder treated after surgery?

- What is the rehabilitation program after rotator cuff surgery?

- How successful is rotator cuff surgery?

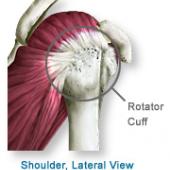

1. What is the rotator cuff?

The rotator cuff is a group of flat tendons that fuse together and surround the front, back, and top of the shoulder joint like a cuff on a shirt sleeve. These tendons are connected individually to short, but very important, muscles that originate from the scapula. When the muscles contract, they pull on the rotator cuff tendon, causing the shoulder to rotate upward, inward, or outward, hence the name "rotator cuff."

2. What is impingement syndrome?

The uppermost tendon of the rotator cuff, the supraspinatus tendon, passes beneath the bone on the top of the shoulder, called the acromion. In some people, the space between the undersurface of the acromion and the top of the humeral head is quite narrow. The rotator cuff tendon and the adherent bursa, or lubricating tissue, can therefore be pinched when the arm is raised into a forward position. With repetitive impingement, the tendons and bursa can become inflamed and swollen and cause the painful situation known as "chronic impingement syndrome."

3. How does impingement syndrome relate to rotator cuff disease?

When the rotator cuff tendon and its overlying bursa become inflamed and swollen with impingement syndrome, the tendon may begin to break down near its attachment on the humerus bone. With continued impingement, the tendon is progressively damaged, and finally, may tear completely away from the bone.

4. Why do some people develop impingement and rotator cuff disease when others do not?

There are many factors that may predispose one person to impingement and rotator cuff problems. The most common is the shape and thickness of the acromion (the bone forming the roof of the shoulder). If the acromion has a bone spur on the front edge, it is more likely to impinge on the rotator cuff when the arm is elevated forward. Activities which involve forward elevation of the arm may put an individual at higher risk for rotator cuff injury. Sometimes the muscles of the shoulder may become imbalanced by injury or atrophy, and imbalance can cause the shoulder to move forward with certain activities which again may cause impingement.

5. Other than impingement, what else can cause rotator cuff damage?

In young, athletic individuals, injury to the rotator cuff can occur with repetitive throwing, overhead racquet sports, or swimming. This type of injury results from repetitive stretching of the rotator cuff during the follow-through phase of the activity. The tear that occurs is not caused by impingement, but more by a joint imbalance. This may be associated with looseness in the front of the shoulder caused by a weakness in the supporting ligaments.

6. What kind of symptoms does a patient have when the rotator cuff is injured?

The most common complaint is aching located in the top and front of the shoulder, or on the outer side of the upper arm (deltoid area). The pain is usually increased when the arm is lifted to the overhead position. Frequently, the pain seems to be worse at night, and often interrupts sleep. Depending on the severity of the injury, there may also be weakness in the arm and, with some complete rotator cuff tears, the arm cannot be lifted in the forward or outward direction at all.

7. How is the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease proven?

The diagnosis of rotator cuff tendon disease includes a careful history taken and reviewed by the physician, an x-ray to visualize the anatomy of the bones of the shoulder, specifically looking for acromial spur, and a physical examination. Atrophy may be present, along with weakness, if the rotator cuff tendons are injured, and special impingement tests can suggest that impingement syndrome is involved. An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan frequently gives the final proof of the status of the rotator cuff tendon. Although none of these tests is guaranteed to be 100% accurate, most rotator cuff injuries can be diagnosed using this combination of exams.

8. What is the initial treatment for rotator cuff disease and impingement?

If minor impingement or rotator cuff tendinitis is diagnosed, a period of rest coupled with medicines taken by mouth, and physical therapy will frequently decrease the inflammation and restore the tone to the atrophied muscles. Activities causing the pain should be slowly resumed only when the pain is gone. Sometimes a cortisone injection into the bursal space above the rotator cuff tendon is helpful to relieve swelling and inflammation. Application of ice to the tender area three or four times a day for 15 minutes is also helpful.

9. What is the second line of treatment if the rotator cuff pain and weakness persist?

If there is a thickened acromion or acromial bone spur causing impingement, it can be removed using arthroscopic visualization. This procedure can often be performed on an outpatient basis, and at the same time, any minor damage and fraying to the rotator cuff tendon and scarred bursal tissue can be removed. Often this will completely cure the impingement and prevent progressive rotator cuff injury.

10. If the rotator cuff is already torn, what are the options?

When the tendon of the rotator cuff has a complete tear, the tendon often must be repaired using surgical techniques. The choice of surgery, of course, depends on the severity of the symptoms, the health of the patient, and the functional requirements for that shoulder. In young working individuals, repair of the tendon is most often suggested. In some older individuals who do not require significant overhead lifting ability, surgical repair may not be as important. If chronic pain and disability are present at any age, consideration for repair of the rotator cuff should be given.

11. What will happen if the rotator cuff is not repaired?

In some situations, the bursa overlying the rotator cuff may form a patch to close the defect in the tendon. Although this is not true tendon healing, it may decrease the pain to an acceptable level. If the tendon edges become fragmented and severely worn, and the muscle contracts and atrophies, repair at that point may not be possible. Sometimes in this situation, the only beneficial surgical procedure would be an arthroscopic operation to remove bone spurs and fragments of torn tissue that catch when the arm is rotated. This certainly will not restore normal power or strength to the shoulder, but often will relieve pain.

12. How is a major injury to the rotator cuff tendon repaired surgically?

The arthroscope is extremely helpful when repairing rotator cuff tendons, but sometimes it is necessary to add a "mini-open" procedure if the tendon is completely torn. Using the arthroscope at the beginning of the case allows visualization of the interior of the joint to facilitate trimming and removal of fragments of torn cuff tendon and biceps tendon. The next step utilizes the arthroscope to visualize the spur and thickened ligament beneath the acromial bone, while they are removed with miniature cutting and grinding instruments. If it is necessary to suture a rotator cuff tear which has pulled off the bone, a two-inch incision can be made directly over the tear that has been visualized and localized using the arthroscope. The deltoid muscle fibers can be spread apart so that strong stitches can attach the rotator cuff tendon back to the bone. If the tear is minimally retracted, small suture screw anchors may be used arthroscopically or open.

13. How is my shoulder treated after surgery?

In a minor operation for impingement, the shoulder is placed in a simple sling. If a full thickness tear of the rotator cuff was present and repaired, then the shoulder will be supported by an UltraSling or a SCOI post-operative brace. The brace is very helpful because it will allow exercise of the elbow, wrist, and hand at all times, and places the arm in a position that promotes better blood circulation and relieves stress on the repaired rotator cuff tissues. In addition, the shoulder can be exercised in the brace much easier than when it is at the side in an immobilizer.

14. What is the rehabilitation program after rotator cuff surgery?

Depending on the type of surgery performed, the program will allow a period of time for healing of the soft tissues followed by time to regain range of motion and then strengthen the shoulder muscles, but particularly the rotator cuff. In minor tendinitis and impingement syndrome, the program takes approximately two to three months. If the rotator cuff tendon has been completely torn, it may take six months or more before the atrophied muscles can resume their function and the range of motion of the arm is restored. Frequently, pain relief is much quicker and return to daily activities is often possible by two to three months.

15. How successful is rotator cuff surgery?

Again, every case is unique. In the young, healthy person with a minor rotator cuff impingement, surgery is predictably successful. As the injury becomes more severe, such as with a large bone spur and fragmentation of the tendon, then a perfect result cannot be expected. Since it is necessary to trim back the unhealthy tendon before reattaching it to the bone, a decreased range of motion of the shoulder will often result. Despite this, pain relief and return of strength are usually well worth the minor decreased mobility. The final outcome often depends on the willingness and ability of an individual patient to work on their post-operative physical therapy program.