Tennis Elbow (Lateral Epicondylitis)

Tennis elbow, or lateral epicondylitis, is one of the most common elbow problems seen by an orthopedic surgeon.

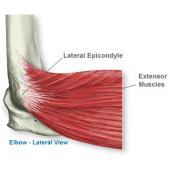

It is actually a tendonitis (medically spelled tendinitis) of the muscle called the extensor carpi radialis brevis, which attaches to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. It may be caused by a sudden injury or by repetitive use of the arm.

Many doctors feel that micro tears in the tendon lead to a hypervascular phenomenon resulting in pain. The pain is usually worse with strong gripping with the elbow in an extended position, as in a tennis backhand stroke, but this problem can occur in golf and other sports as well as with repetitive use of tools.

Before surgery is considered, a trial of at least six months of conservative treatment is indicated and may consist of a properly placed forearm brace and a combination of elbow activity modification, anti-inflammatory medication, and physical therapy. If the above treatment is not helpful, a cortisone injection can be beneficial, but no more than three injections are recommended in any one location in a year.

Conservative treatment is in two phases, and after Phase I (pain relief) has been successful, Phase II (prevention of recurrence) is equally important and involves stretching and later, strengthening exercises, so the micro tears will not occur in the future.

When conservative treatment has failed, then surgery is indicated. Many procedures have been described. Procedures as simple as percutaneous release of the tendon off of the bone have been described and more recently, arthroscopic procedures or other procedures involving the joint and resection of a ligament as well have been described.

The most popular procedure today is a simple excision of diseased tissue from within the tendon, shaving down the bone, and re-attachment of the tendon. This can be performed as an outpatient procedure with regional anesthesia (where only the arm goes to sleep), and through a relatively small incision of approximately three inches. Eighty-five to ninety percent of patients who undergo this procedure are typically able to perform full activities without pain after a recuperation of two to three months. Approximately 10-12% of patients have improvement, but with some pain during aggressive activities, and only 2-3% of patients have no improvement.